Over the past few months, North Korea has been been in the headlines even more than usual. A partial list includes a revelation through the Wikileaks documents on the Afghanistan war that Osama bin Laden’s money man flew to North Korea to buy weapons, the seizure of a South Korean fishing ship (again) and threatening to blow the entire peninsula to hell because South Korea accused the North of sinking one of its ships. Most recently we’ve seen Jimmy Carter travel to Pyongyang to secure the release of Aijalon Gomez, an American who was sentenced to eight years of hard labor after straying across the border into North Korea from China. During his seven-month imprisonment, Gomez was driven to such despair by the experience that he attempted to commit suicide.

It’s common knowledge that there’s something terribly amiss in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK); this is no revelation. Even China has begun to inch slowly away from the Kims. In June, the People’s Republic finally admitted, after more than five decades, that North Korea actually did provoke the Korean War by invading the south.

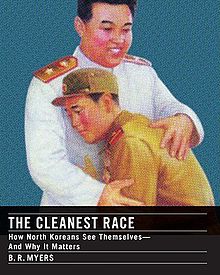

But according to Atlantic contributing editor B. R. Myers’ new bookThe Cleanest Race: How North Koreans See Themselves and Why It Matters, North Korea might be even stranger—and worse—than we could have imagined. Long considered an extreme Stalinist or Communist state, Myers argues that its ruling ideology has more in common with that of Hirohito than Lenin. In reality, we’re dealing with a racially-based dictatorship that is “eternally” “led” by a president who’s been dead since 1994, and which is modeled on the regime that then-fascist Japan imposed on the entire peninsula.

In 2006, at a widely reported meeting between North and South Korean delegations, the issue of “race-mixing” was brought up by the northern delegates. The South Korean said that all of the non-Koreans in his state amounted to a drop of ink in the Han River. The reply from the North: “Not even one drop of ink must be allowed to fall into the Han River.”

And consider the following:

Mono-ethnicity is something that our nation and no other on earth can pride itself on…There is no suppressing the nation’s shame and rage at the talk of “a multi-ethnic, multi-racial society” …which would dilute even the bloodline of our people.”

You may be surprised to find out that this quote isn’t from the Nazi Party or David Duke; instead it is from the April 27, 2006, edition Rodong Sinmun, the official paper of the Workers Party, the group that rules the “DPRK” (at least the “K” for “Korea” is honest), as translated by Myers.

Even during the days of the Communist bloc, North Korea was seen as an outsider, something different from the other countries that espoused Marx and Lenin (the DPRK, it has to be noted, began distancing themselves from these foreigners decades ago). The USSR and the rest of the bloc at least gave lip service to raising living standards, for example. In contradiction, Kim Il Sung is quoted as saying to the then leader of East Germany that if the people’s living conditions rise too much, they become lazy.

The DPRK goes out of its way, as Myers documents, to portray all foreigners as evil figures. Americans are hook-nosed, dark-skinned “jackals.” And the way that they portray the Japanese is even worse. Forgive the long quote (quoted by Myers) from a popular novel about the war of liberation against Japan:

Kumchol could feel his bitter heart begin to open, the heart that could only open at the sight of Japs’ blood…The Jap’s neck glistened greasily like a pig’s. When Kumchol saw it the fire in his breast raged intensely…He yanked the bastard up by the neck and dragged him out of the box, where he fell down again. Seeing he had pissed on the papers in the box from fear, Kumchol spat on his pale mug…Unable to speak, the Jap bowed his head and pressed his hands together, pleading soundlessly for mercy. “Son of a bitch! So you don’t want to die?” …Kumchol wanted to cut the swine’s neck open with his own hands…

And what happens when the “Jap” tries to run away? Our hero kicks him in his skull and “the eyeballs sprang out of their sockets as the skull splattered against the barrack wall.”

We don’t have to look far to find racial myths springing into action: North Korea’s national soccer team, especially Kim Jong-hun, the coach, were perhaps the most recent victims of the racial state. The team committed the sin of losing to Brazil—and on national television, as a live broadcast had been allowed for the first time. What followed was easy enough to guess beforehand: the team was paraded in front of the nation, forced to face criticism, then self-criticism. The worst fate was reserved for the coach, who was made to “confess” that he betrayed the great leader and was, as punishment for his crime, forced to become a worker without a party: his membership in the ruling Workers Party of Korea was stripped, and he was sent to a labor camp.

In a state that so identifies with race and racial superiority, the idea that the national team lost simply because it wasn’t good enough, as compared to other nations, to win simply cannot be allowed. One might argue that this is nothing new in totalitarian societies, but, in the Korean example, who was spared is as telling as who was not. Only one player who returned to the country escaped any harsh punishment: Jong Tae Se—who was born in Japan. With a populace fully if forcibly enraptured in delusions of its own superiority, there is no need to explain the failures of the player who can so easily be identified with the Japanese, both racial inferiors and degenerate war criminals by DNA.

Myers postulates the official myth as follows: the Korean people are not particularly stronger or smarter than other nations, but they are uniquely virtuous, compared to all others. In their virtue, they are a child-like race, and they therefore need a great leader who acts like a mother (as the Kims are often portrayed) and as a defender from the evil outside world. Myers documents the North Korean propagandists’ use of stories about the two Kims, as well as even seemingly apolitical art, to portray a sturdy resolve of the Korean nation—the race—against outsiders.

According to the regime’s propaganda, not only is the outside world trying to kill off North Korea, but it is also fully engaged in bizarre, immoral acts—like homosexuality, a very American “perversion.” In another popular novel, after the USS Pueblo is captured, one of the American sailors is depicted as asking for permission to have sex with the rest of the male crew. The response: “This is the territory of our republic, where people enjoy lives befitting human beings. On this soil none of that sort of activity will be tolerated.”

This belief system has taken its toll not only on the people of North Korea, but on even diplomats from socialist countries as well. Myers describes how a Black Cuban ambassador, trying to show his family the sites of Pyongyang, was nearly lynched by a local mob.

One race is superior and blood should not mix; homosexuality is an evil perversion; Black people are beaten by locals; certain nationalities are fundamentally evil: this is the stuff of North Korean “socialism,” and very little of it can be considered alien to al-Qaeda’s interpretation of Islam.

Myers argues that, to create an appropriate policy towards the DPRK, these facts have to be taken into account. For example, he makes the case that the regime needs animosity towards, and from, the U.S. (and to the government in the south) to justify its existence. If this is the case, then any real peace treaty with the U.S. would jeopardize the regime’s existence, and actually signing a peace treaty with North Korea would, far from strengthening the ruling Kim dictatorship, strike a blow at the state’s very foundations.

Of course, the similarities and working relationships between North Korea, Islamic fundamentalist groups and other reactionary organizations and states only go so far, and it is improbable that there is an organized North Korea/al-Qaeda cabal working together on any level higher than pure business. After all, it is highly unlikely that the two groups would come to agreement over which god, Allah or Kim, is greater.

Nonetheless, recognition of the true nature of the regime occupying the northern half of the Korean peninsula can only help to inform future policy discussion and decisions regarding an area of the world where, as the DPRK’s press routinely informs us, “war may break out at any moment.”

Originally published in Guernica at www.guernicamag.org

Rotten Apple: iPod sweatshops hidden in China

Originally published January 25, 2011

Apple, famous for its Mac computers and iPhones, spends millions to create the image of a benevolent corporate giant that, while making money, does more than its part to better the world.

But a new study by China’s Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs sharply contradicts this claim. The report, The Other Side of Apple, slams the corporate behemoth for mistreating its workers and poisoning the environment.

“Behind their stylish image,” reads the introduction, “Apple products have a side that many do not know about – pollution and poison. This side is hidden deep within the company’s secretive supply chain, out of view from the public.”

Apple, according to its social responsibility website, ensures “that working conditions in Apple’s supply chain are safe, that workers are treated with respect and dignity, and that manufacturing processes are environmentally responsible.”

The IPE investigated, clearing away “some of the dense fog that enshrouds” the highly secretive company. IPE was able to piece together a list of “suspected” suppliers. It seems certain that these suspects actually do supply Apple, for several reasons; employees, for example, mention that Apple representatives came to the factories often. Further, many of the products were produced with the iconic Apple logo.

Suppliers – Apple has no factories of its own – routinely violate China’s “Law on the Prevention and Control of Occupational Diseases.” Several manufacturers replaced alcohol, used to clean parts, with n-hexane, a chemical that works better than alcohol – but poisons workers. Because of the chemical in suspected supplier Lian Jian Technology’s plant, Suzhou No. 5 People’s Hospital admitted 49 employees who fell ill. More employees were likely poisoned, but many were pushed out before they fell ill, and Lian Jian forced them to sign papers saying they would not hold the company accountable.

“They left with 80 or 90 thousand yuan [$12 – $14,000],” said a Lian Jian worker, “that they got in exchange for their lives and health, with fees and medical costs they would have to pay for the rest of their lives.”

In these factories, the workers, often women in their teens or 20s, were forced to work with the poison in unventilated rooms.

Xiao Zhan, a 19-year-old who was poisoned at Yun Heng Hardware and Electrical, where Apple logos were polished, described in her blog how she and her coworkers became more and more sickened by the poison, until they eventually needed intensive medical treatment.

In less than six months, 12 employees of Foxconn, “Apple’s largest supplier in China,” committed or attempted to commit suicide by jumping from buildings. This, according to the study, “shocked the nation. Chinese society began to rethink how best to give workers proper respect…”

The local government checked 5,044 workers, finding that 72.5 percent had been forced to work more overtime than legally allowed. Many have blamed the harsh working conditions on the suicides.

Workers at Dafu, another plant, were forced to undergo extreme humiliation. Female workers were searched – they were forced to remove clothes – in full view each time they left work.

“Watching a younger girl stand on the inspection platform with her pants suddenly falling down and run away as everyone laughed at her,” said one worker there, “my eyes filled with tears and I did not laugh.” It wasn’t until Chinese authorities forced the plant to establish trade unions that conditions began to improve.

Further, many of these suppliers have been cited by Chinese authorities for far exceeding the amount of toxic waste allowed by law.

How can Apple get away with this? the IPE asked. The answer: the “culture of secrecy,” doesn’t only hide trade secrets, but suppliers’ identities – and abuses of workers and the environment.

In a typical response to questions from an NGO, Apple wrote July 15, 2010, that they “will not disclose any information about suppliers, including anything about an investigation, its timing and/or the results of the investigation.”

China’s NGO network, the Green Choice Alliance, monitors corporate polluters. Numerous companies, even Wal-Mart and Nike, are working with the GCA and “many best practices have emerged.” About 330 companies so far are participating – but not Apple.

Apple stands alone even among other IT companies – which routinely cause problems of heavy metal pollution – in its evasiveness and refusal to work with green groups.

Socialist China has empowered its trade union movement – which is backed by the government – and has been attempting to strengthen regulatory laws. However, even the Chinese state has great difficulty in enforcing fines and penalties when companies – primarily foreign – violate labor and environmental laws.

As the report notes, the problems in China are typical of many developing countries, which “make and export cheap products; however the pollution is then dumped in their own backyards.”