I realize that the title of this post sounds crazy. The idea that a member of the Worcester City Council is defending a terrorist organization that has vowed to wipe out the world’s Jews, an anti-Israel and anti-America organization aligned with Iran, and through them Moscow and Beijing, sounds positively unhinged. Still, facts are facts.

Further, Nguyen’s defense of Hamas did not come out of nowhere; it fits into an escalating pattern of extremism on the part of the city councilor.

Background

On October 17, Nguyen was one of only two city council members to vote against a resolution stating that Worcester would “condemn the recent barbaric and inhuman taking of hostages in Israel, including a number of American citizens, and prays for their immediate and safe release and return to their loved ones.”

Nguyen made a rambling statement before casting their vote against the resolution. While they made a token, sentence-long condemnation of the violence of Hamas, Nguyen repeated uncritically that organization’s propaganda, including that Israel was going to commit “genocide” against Palestinians and that the IDF, Israel’s military, had bombed a hospital, killing 500 people.

Even before Nguyen spoke, details had already emerged showing that it was extremely unlikely that Israel had bombed the medical facility. We now know, as the U.S. intelligence community has asserted with “high confidence,” that the explosion was due to a projectile misfired by the terrorist Palestinian Islamic Jihad, which had been aimed at Israel. While the “fog of war” was still heavy as the council meeting was ongoing, Nguyen doubled down on this false assertion the next day, October 18, the same day the president told the world Israel was not responsible.

The best-case scenario is that they are posting inflammatory rhetoric about something of which they are entirely ignorant. But Nguyen’s pattern of behavior suggests something more sinister.

Next fact.

As mentioned above, Nguyen stood in a public forum and accused Israel of “genocide.” No one who understands the definition of the term really believes that Israel is engaged in this crime against humanity, and we know that Nguyen had been made aware that this false accusation is an anti-Jewish blood libel. On October 16, Nguyen posted an image from a group called “Jewish Voice for Peace,” a non-Jewish organization (in fact, the founder of one of its chapters was a Muslim Palestinian-Jordanian also on the board of a group the U.S. government listed as a non-indicted co-conspirator with Hamas). According Anti-Defamation League, JVP is as an extremist group that uses antisemitic imagery and endangers Jews.

That day, I reached out to Nguyen via social media, as chronicled here, with a link to the ADL statement and, trying to appeal to Nguyen, said that using JVP as token “Jews” to advance such rhetoric was similar to using Candace Owens as the “voice of the Black community.’ It’s certain that Nguyen read the message, because they replied, saying glibly, “More like Angela Davis.” Nguyen therefore knew that they were spreading the views of an extremist organization engaged in antisemitism.

On Oct. 22 and 28, Nguyen published one-sided “free Palesitne” statements. The irony here is that as an excuse for voting against the resolution calling to free the hostages, Nguyen said “we need to grieve the death in both communities.” But Nguyen hasn’t done that: they spared only one throwaway, milquetoast line was given to the 1,400 innocent people who were slaughtered and raped by Hamas, and yet have written post after post on social media about Palestine and are urging people to a “free Palestine” demonstration, spreading Hamas propaganda and blood libel in the meanwhile.

Maybe the reader is asking, “Okay, the above evidence paints a picture of a person who is clearly anti-Israel and doesn’t care about the welfare of Jews, but can you really accuse Nguyen of supporting Hamas based on this?”

Thu Nguyen in support of Hamas

The answer is, of course, no. There are many different types of Israel-haters and antisemites; they don’t all support Hamas. But Nguyen cleared up any confusion we might have had on October 25.

On that day, Nguyen – the supposed defender of women’s rights – posted a defense of the organization whose members on October 7 raped girls so forcefully their pelvic bones were broken.

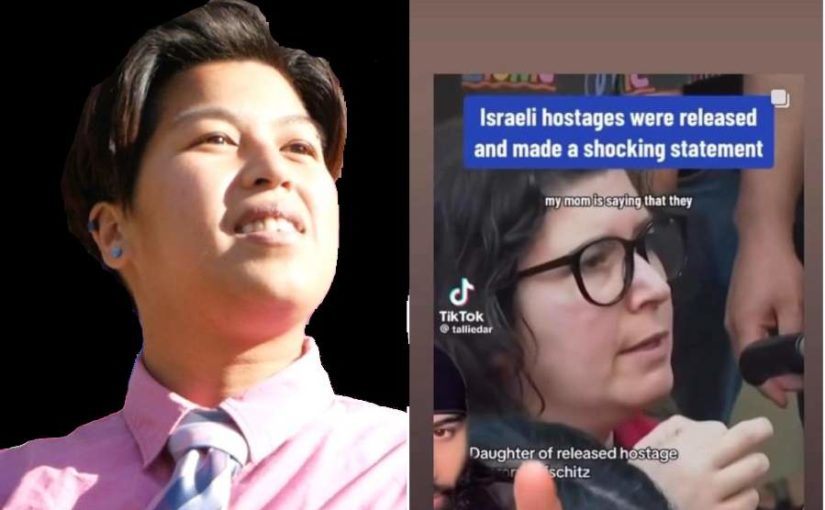

That’s right: a sitting Worcester city councilor told us via social media that the organization that slaughtered 1,400 people and kidnapped 200, including a six-month-old baby, is really not as bad as people think. Nguyen did this by linking to a video on Instagram showing hostages Hamas released saying that they had been treated well in captivity. The video concluded with a man insinuating that CNN had lied when the hostages said they “went through hell.”

Of course, the same hostage did say she went through hell. Being captured by a murderous group of thugs and brought to a foreign land isn’t pleasant. What Nguyen’s link failed to mention was that the husband of the former hostage is still locked in Gaza, dramatically limiting her ability to speak freely. And even if that weren’t the case, Stockholm Syndrome is extremely well known.

There is no possible reason imaginable that Nguyen would post this to their official campaign page except that they are sympathetic to the U.S.-designated foreign terrorist organization. And when I pointed this out on social media, they doubled down.

Instead of responding in a normal way – “I regret this terrible oversight, which certainly does not reflect my views,” etc. – Nguyen posted the following:

An aside

Let’s look at what Nguyen thinks, based on this statement. Even if they weren’t an antisemitic Hamas supporter, is this the kind of person who should represent us?

Someone who believes that constituents condemning their representative’s blood libel and support for Hamas on social media is a “stalkerish obsession”?

Someone who believes that, in a democratic system, when your representative comes out in support of terrorists – or, really, anything with which you disagree – you’re supposed to just “leave them alone”?

Someone who thinks “fearmongering” is the same as “look at what this person said”?

Someone who thinks criticizing a politician via social media is “intimidation”?

Anyway, I responded via X.

Nguyen still refuses to denounce Hamas

And Nguyen responded, almost incomprehensibly:

I responded that calling someone a “stalker” is slanderous, and Nguyen immediately removed that post and then blocked me on Facebook (which is not actually legal for municipal representatives to do on non-personal pages).

How can anyone believe Nguyen doesn’t sympathize with Hamas?

Thu Nguyen posted a link defending Hamas from accusations that they made the lives of the people they abducted hell. What other explanation could there be? Nguyen responded to criticism of their defense of the anti-Israeli, anti-American terrorist group that holds the people of Gaza captive by deflecting, by insulting one of their constituents. Why would they do this if they didn’t support Hamas? What possible reason could there be? There’s only one possible answer, unless we hear otherwise.

Thu Nguyen supports Hamas.