Recently, I dusted off a copy of Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man, first published in 1992. What I found is that, despite the derision the idea of history’s end has received over the past few decades, Fukuyama’s book is in retrospect a surprisingly prescient work that helps to make sense of the current period.

Recently, I dusted off a copy of Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man, first published in 1992. Despite the derision the idea of history’s end has received over the past few decades, Fukuyama’s book is turned out to be a surprisingly prescient work that helps to make sense of the current period.

The end of history

The first part of Fukuyama’s argument is well known. Basing himself on Hegel and, especially, the interpretation of Hegel by the German philosopher’s student Alexandre Kojève, Fukuyama argued that history wasn’t just a bunch of events that happened one after the other. Instead, history advanced in a progressive direction. The outcome, or natural endpoint, of history was liberal democracy, the kind enjoyed by citizens of the United States, France, and other countries.

While Fukuyama was criticized for positing the American model as history’s outcome, he never did so, instead seeing liberal democracy more broadly defined, as some kind of parliamentary system that allows for citizens to express their desires politically and a market economy economically, all accompanied by the rule of law.

In 1989, when Fukuyama first wrote the essay that later became the book, liberal democracy was obviously triumphant. The Berlin wall had just fallen, the Cold War had ended, and the NATO alliance was the victor as the Soviet Union bowed out of superpower status. China was convulsed by uprisings, and the Communist Party there only maintained its grip on power through sheer brutality. Over the course of the next three years, Communist states fell quickly and dramatically, the culmination of what political scientist Samuel Huntington later declared “the third wave” of democratization.

History’s rebirth?

In the intervening years, however, the picture became muddied. Some of the post-Soviet states went through a period of “democratic backsliding,” in which they reverted to autocracy, as did Venezuela and a few other states. After 9/11, another of Huntington’s ideas, that the world would cease to be torn by ideological divides and would become defined by “civilizational” struggles. seemed to take on new credence. Two of the “civilizations” Huntington outlined, the Islamic and the Western, appeared to be the world’s major faultline, while the “Orthodox” (the Orthodox Christian states of the former Soviet Union and several of its allies) seemed to be only slightly less antagonistic.

The Arab Spring of 2011 and the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2014, as well as the less antagonistic relationship between the Muslim and Western world (note, especially, the Abraham Accords between Israel and several Arab Muslim states) essentially put the clash of civilizations theory to rest. But there was another challenge to Fukuyama’s “end of history” theory.

For Fukuyama and his reading of Hegel through Kojève, history didn’t progress in some sort of pre-ordained and mechanical way as it does in the Marxist interpretation of Hegel. Instead, liberal democracy is the end state simply because it works better than any other model tried. By spreading out decision making both economically and politically, it allows people to participate in the affairs that interest them and avoids disastrous mistakes of policy like those the Soviets often made. The then-rising “China model” of authoritarianism challenged the theory, however.

The China model

Disappointed that government wasn’t “getting things done,” especially in the early 2010s, many western intellectuals looked to China and saw the benefits of an authoritarian state. Perhaps, they wondered, by limiting the mess of democracy, technocrats in China were able to move their society forward rationally and impartially, elevating only the best people to leadership through a meritocratic model. “I disagree with the view that there’s only one morally legitimate way of selecting leaders: one person, one vote,” Daniel Bell said at an Asia Society discussion entitled “Can the China Model Succeed?”

Then the pandemic happened, and, for a while, and despite ample evidence that the Chinese authorities mismanaged the outbreak from the beginning (despite heroic work done by Chinese doctors and scientists), Western public health experts began to fawn over China. Greg Ip argued that the “Zero-Covid” policy “held lessons” for others in the pages of the Wall Street Journal. Public health experts from Duke and UC-San Francisco wrote in Time that China’s response was “100 times better” than that of the United States.

The late 2010s were a bad time for liberal democracy, with the chaos of Trump’s presidency followed by the similar chaos of Biden’s presidency, unable to deal with crime or inflation or virtually any other problem the U.S. faced; Brexit in the United Kingdom; anti-liberal democracy parties elected into governments in a host of Western democracies, including Brazil; and so on. But then things changed.

1991 redux?

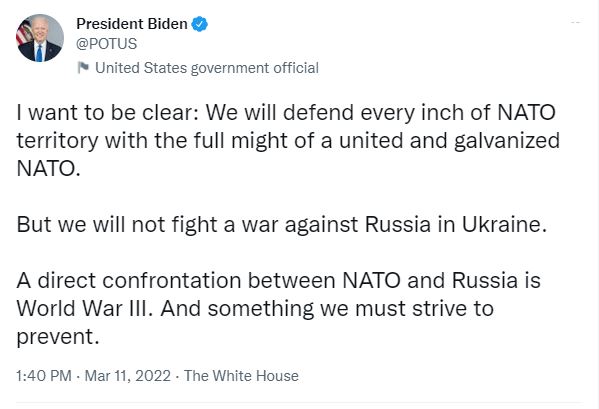

In 2022, around the world, people began again fighting in earnest to free themselves from tyrannical systems. As the year began, Russia invaded Ukraine.Though most everyone thought Russia’s invasion appalling, they also expected Putin’s onslaught to succeed relatively quickly. Then the Ukrainians took history into their own hands. Surprising the world and, perhaps, even themselves, the Ukrainian people united together to issue a forceful response to the Russian aggressors. Instead of quickly annexing Ukraine, Russia was forced into a long slog.

Russia had expected the various factions in Ukraine, constantly fighting each other – as the current political factions in the United States fight each other – would fold. Instead, they put aside their differences and began to save their country.

As the Ukrainians inspired the world, the Iranian regime arrested and murdered a 22-year-old Kurdish woman named Mahsa Amini for the “crime” of not wearing her hijab “correctly.” The evil act proved the spark that set off the Iranian tinderbox: across Iran, women, and then men, rose up, demanding an end to their oppression. Across the nation, the morality police and other regime thugs responded in the harshest ways possible, gunning down protesters – women, children, men – in the streets. And yet the Iranians keep fighting: in the streets, on TikTok, on Twitter, everywhere, they fight. Even the Ayatollah’s own niece condemned the regime, signaling a total loss of legitimacy. Backed into a corner, the theocracy has just announced it would abolish its morality police, and now even the hijab law is under review.

The people of Iran are still fighting, likely for liberal democracy.

And now, even China, the prize of the authoritarian model, has erupted in protests unheard of since 1989. As demonstrations raged against the harsh “Zero Covid” police that so enchanted Western technocrats months ago, Chinese authorities cracked down, with videos flooding social media platforms depicting the barbarity. And now, China has begun to back off, easing restrictions. While it’s unlikely that the Communist Party will fall anytime soon, the luster of the China model has been removed.

There is no civilizational struggle and the authoritarian model is not a path anyone wants to follow; those who live under it do so until they have a chance to overthrow it. Despite the detours, we’re still at the end of history.

The other part of Fukuyama’s argument

Part of the reason some have rejected the “end of history” thesis is because of the problems that have become so common liberal democracies, as mentioned above. But these are issues that Fukuyama mentioned in his book (though, not the original article, suggesting that many of those disparaging the book never read it). Challenges that we face are challenges listed in the End of History: income inequality, political decay, and the fraying of social bonds, and the human need for recognition.

A sizable portion of End of History is dedicated to a discussion of thymos, the human need for recognition. Thymos was the impetus for much of history’s forward movement, according to this understanding of Hegel. The fact that some are so driven for status and recognition that they would fight and kill for some cause led to the acts of valor (or butcherie, depending on the moral viewpoint and the actions carried out) that caused war, revolution, and so on. Fighting against oppression is often caused by an injury to one’s thymos: Fukuyama gives numerous examples, including a speech by Vaclav Havel, in which the latter describes the injury to his self-esteem done by Czechoslovak communism.

The question Fukuyama posed about the future of liberal democracy: what happens in a system where thymos isn’t, and can’t be, a motivating factor? Will society become composed of “men without chests,” satiated consumers with no will to fight? As Alexis Carré notes in Foreign Policy, Western Europe, long stable and under the defense of the United States, has weapons but no warriors.

Given the discussion of thymos and the quest for recognition by others, it is hard to understand why so few have made the connection between End of History and the current period in the Western world, in which identity politics, including white identity politics, has come to the fore so prominently. Even those not consumed by identity overtly have become quite tribal in their partisan allegiances. Keyboard warriors, unable to fight on the battlefield, rage-type on Twitter. Is it any wonder that one of the biggest controversies of the day revolves around who gets to say what on a social media platform?

The book suggested the general dynamics of this world decades ago.

History is still over, and Fukuyama’s work has been vindicated. Regardless of any challenges, the liberal democratic system has proven itself to be the best system possible because it best meets the needs of those who inhabit it. No other system, looking back centuries, has been able to outlast it. Where there is no liberal democracy, people are fighting for it.

As Jesus Jones put it, we’re all still “watching the world wake up from history” in China, Iran, Ukraine, Russia, and other places where it’s not fully over. The rest of us, residing where history still lies dead, have to solve the challenge thymos poses in liberal democracy.